Deportees Learn Workforce and Life Skills at Tijuana Migrant Shelter

By: Sandra Dibble

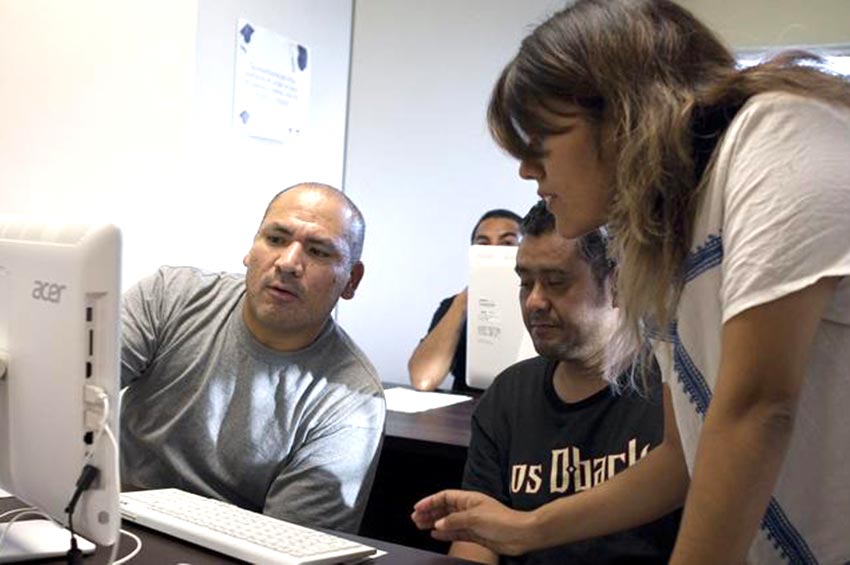

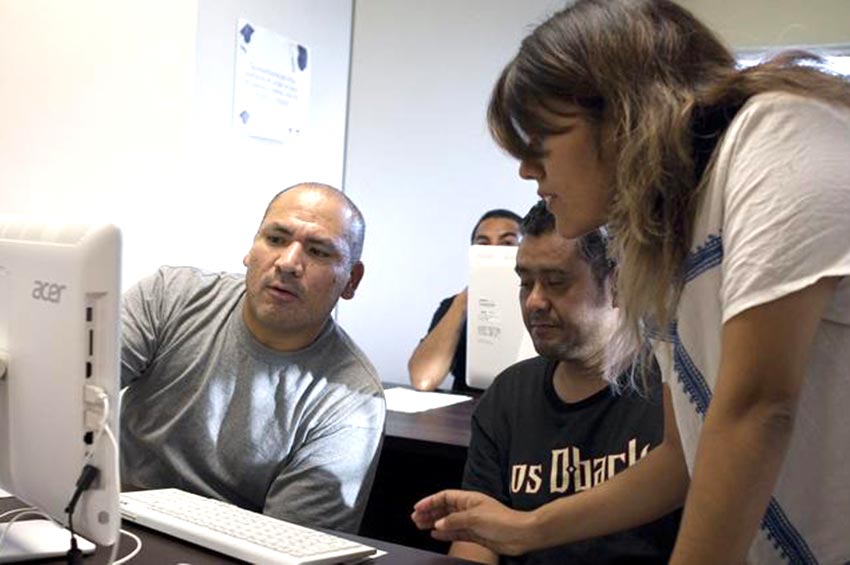

In more than two decades working construction in south Texas, Raúl Vanegas had no time for school of any kind. But a day after being deported to Tijuana, the 43-year-old native of San Luis Potosí found himself inside a small classroom, studying the basics of operating a personal computer.

“I didn’t even know how to turn one on,” Vanegas said smiling broadly as he finished a two-hour class at the Casa del Migrante, Tijuana’s oldest and largest migrant shelter. “I feel like a kid. Today, I think I moved forward 200 percent.”

The computer course is one of a number of classes at the shelter that are aimed primarily at U.S. deportees, but also open to other migrants making the transition to being in Mexico. It gives them a chance to acquire new job skills, obtain equivalency certificates, study Spanish, and learn to navigate the internet.

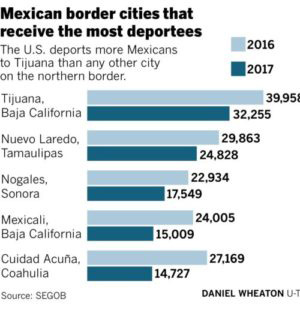

Tijuana receives tens of thousands of U.S. deportees annually, more so than any other city on Mexico’s northern border, according to with Mexico’s National Migration Institute. Last year, 32,255 deportees were sent back through the city—a rate of 88 per day.

As the deportations continue, and are expected by some to increase, this creates new demands for shelters like the Casa, once filled with Mexicans heading north to the United States, and now flooded with Mexicans forced to return.

As the deportations continue, and are expected by some to increase, this creates new demands for shelters like the Casa, once filled with Mexicans heading north to the United States, and now flooded with Mexicans forced to return.

“This used to be a place to sleep, eat, rest for a few days,” said José Carlos Yee, coordinator of the Casa’s new educational center, Centro Scalabrini de Formación de Migrantes. “Now it’s just the opposite, they’re not leaving, and that demands a lot more work.”

Vanegas, a sixth-grade graduate who first crossed into the United States when he was 14 years old, was back in Mexico, and this time for good, he said. His four children live in the United States, as do both of his parents, but going back is not even a dream anymore: He has been deported before, and if caught again attempting to return, he faces a lengthy sentence, he said.

A grandmother in Mexico lives in the border city of Reynosa, “but it’s very dangerous there,” he said, and he prefers to make his way in Tijuana, where he can communicate with family and look forward to their visits.

He’s eager to learn about computers, so that he can talk to his children through Skype and Facetime. But he also hopes the new skills can be the key to better work opportunities in Mexico.

“People ask if you know how to use a computer, and if you tell them no, they look at you as though you just stepped out of a cave,” he told his classmates, provoking a ripple of laughter.

Vanegas, who arrived in Tijuana with $200 in his pocket, typifies the kind of person who comes to the shelter’s door these days. Part of a network of Catholic shelters operated by the Scalabrianian missionary order, the Casa del Migrante provides shelter for as many as 179 people a night, almost always men, and these days 90 percent of the population are deportees.

At the shelter, they find beds, food, medical attention, legal help, psychological counseling, spiritual support, phones to call family members, and contacts for job possibilities.

Since May, they’ve also been able to take classes in Spanish and computer literacy and sit for equivalency exams for elementary and junior high school offered onsite by Mexico’s National Institution for Adult Education, INEA. Though the center’s classes are currently being held onsite at the shelter, by September they will be in a separate structure being prepared a few blocks away.

The plan is to soon add vocational classes on subjects such as cutting hair, hydroponics, building vertical gardens, caring for endemic plants — skills that can help deportees move forward. In surveys at the Casa and other shelters around the city, staff have found that the biggest demand has been for a class in basic electrical installations, and Yee, the program director, said the first one is expected to launch this month.

On Tuesday evening, Vanegas was among the class of 12 men and one woman sitting intently before computer screens. As light streamed through the window, a video played a reading by the Argentinian singer Facundo Cabral.

“You are not depressed, you are distracted,” Cabral’s voice called out. “You are distracted from the life within you, you have a heart, a brain, a soul, a spiirt.”

The assignment was to type a few sentences about the message, share it out loud with the group, then master the technical task of defining and changing the size and color of the type, and finally saving the file to the computer.

With most of her students struggling from the trauma of deportation, family separation and uncertainty about the future, teacher María José Juárez strives to not just teach skills, but strike an encouraging tone.

“This is a place of safety, of respect, of togetherness,” she said. “We want them to say, “I have all the tools, I have all the abilities to move forward, and nobody can take them away from me.”

sandra.dibble@sduniontribune.com

* Repost from: San Diego Union Tribune 07/10/2018

Suscríbase a nuestra lista de correo

Manténgase en contacto con el ICF

Sea el primero en recibir información exclusiva sobre lo que hace ICF para marcar la diferencia.

Los campos marcados con * son requeridos